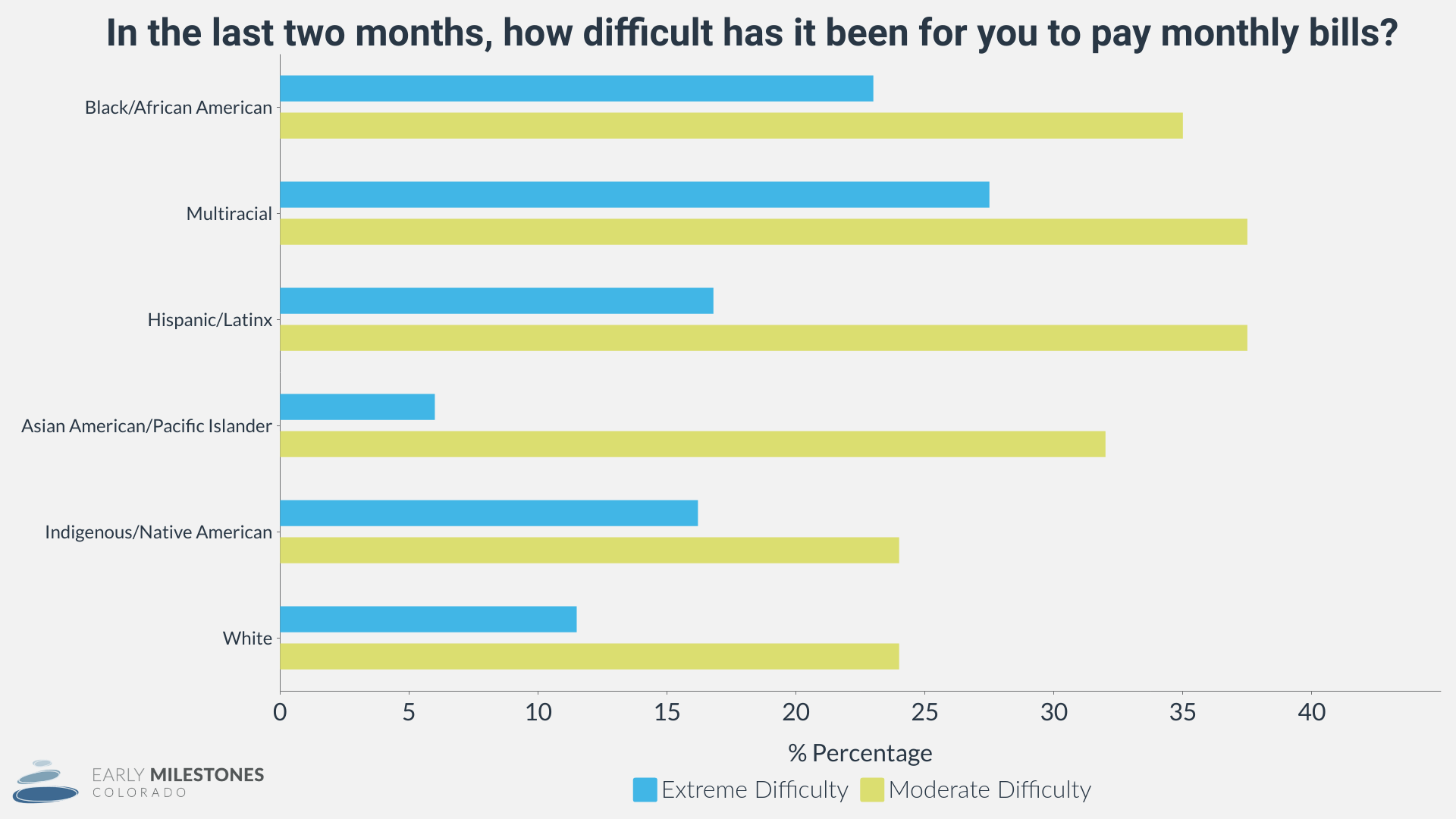

In 2021, Colorado families dealt with social and economic hardships. These hardships were more pronounced for families of color, and those headed by single women.[1] A year later, the economy had shifted, with more job opportunities but also more inflation. To learn how Colorado families were doing, we conducted a final survey in April 2022. We heard from 2,174 families who all had at least one child 6 or younger.

Mental Health Challenges Persist for Families with Young Children

Last year, families continued to struggle with financial strain, work disruptions, limited childcare, social isolation, and other stressors.

“Our dismal financial situation is, by far, the largest source of mental health challenges.” – White Father, Gilpin County

“[I’m] still suffering the mental toll from taking a pay cut and step back professionally due to pandemic layoffs.” – White Mother, Douglas County

“There is almost constant sickness in the house disrupting social time, routines, adding stress, anxiety, and lots of doctor visits.” – White Mother, Jefferson County

Translated from Spanish: “The price of food and housing [is] very high, also electricity, water…everything is more difficult since COVID.” – Latinx Mother, Denver County

Overall, only 26% of parents and caregivers said their mental health was fair or poor. Many people felt less stress in Summer 2022 than they felt earlier in the pandemic.

“Mental health has improved because I enjoy my new career, because I was able to finally memorialize my father who died [during the] pandemic, and because I see my friends.” – White Mother, Jefferson County

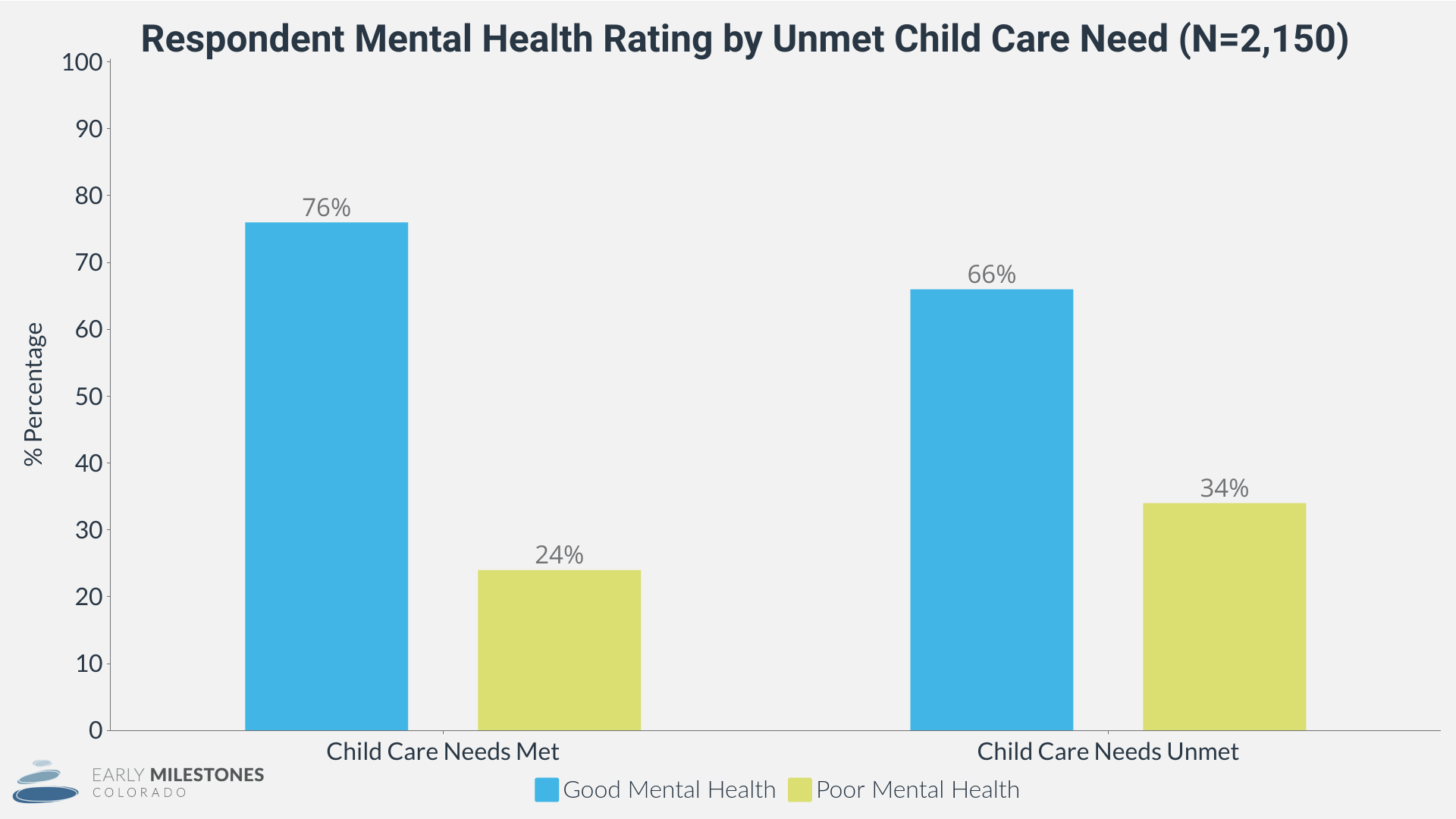

The 2021 Colorado Health Access Survey found that struggles with money and accessing child care correlated with mental health challenges and poor general health among parents. In our 2022 survey, caregivers with household incomes lower than the Colorado median of $75,000 per year were more likely to report poor mental health than those with higher incomes. Thirty-four percent of caregivers who did not have the child care they needed reported poor mental health compared to 24% of those who did have child care.

Parents with unmet child care needs (26%) were also more likely to report that their mental health had gotten worse in the first quarter of 2022 than those with adequate child care (16%).

“I took days off work to cold-call 66 child cares to try to find a new spot for my daughter when we needed to leave her current daycare. It’s the most stressed I’ve ever been.” – White Mother, Jefferson County

Caregivers dealt with continued worries and anxiety. Lower-income families were less likely to say they had emotional support.

Research has shown that children thrive when the adults in their lives are supported mentally and emotionally.[2],[3] Nationwide, parents’ stress, family violence, and financial insecurity increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and children’s behavioral health suffered.[4]

The caregivers in our survey reported a range of stressors, many of which have been worsened by the pandemic. Forty-four percent of caregivers with poor mental health said that the extra time required to provide direct child care had impacted their well-being.

Respondents also listed financial concerns, health concerns, and family instability when asked about other recent impacts on their mental health.

“Price of everything and not having enough money for necessities.” – Black Mother, Denver County

“Having to work almost full time just to cover rent and not even that. Now TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), [which] allowed me to make rent, tells me I’ll only have childcare for 3 days, and because I get child support, they will take away the money I need to have a place to live.” – White Mother, Douglas County

“Concern over keeping career or staying home to care for child.” – White Mother, Denver County

Families were struggling to get support to deal with ongoing stress. Lower-income families especially needed support. Only 42% of low-income caregivers said they had enough emotional support to deal with pandemic stressors compared to 52% of higher-income caregivers. Parents also said that mental health services were hard to access.

More than 1 in 4 parents worried that their child had a developmental delay.

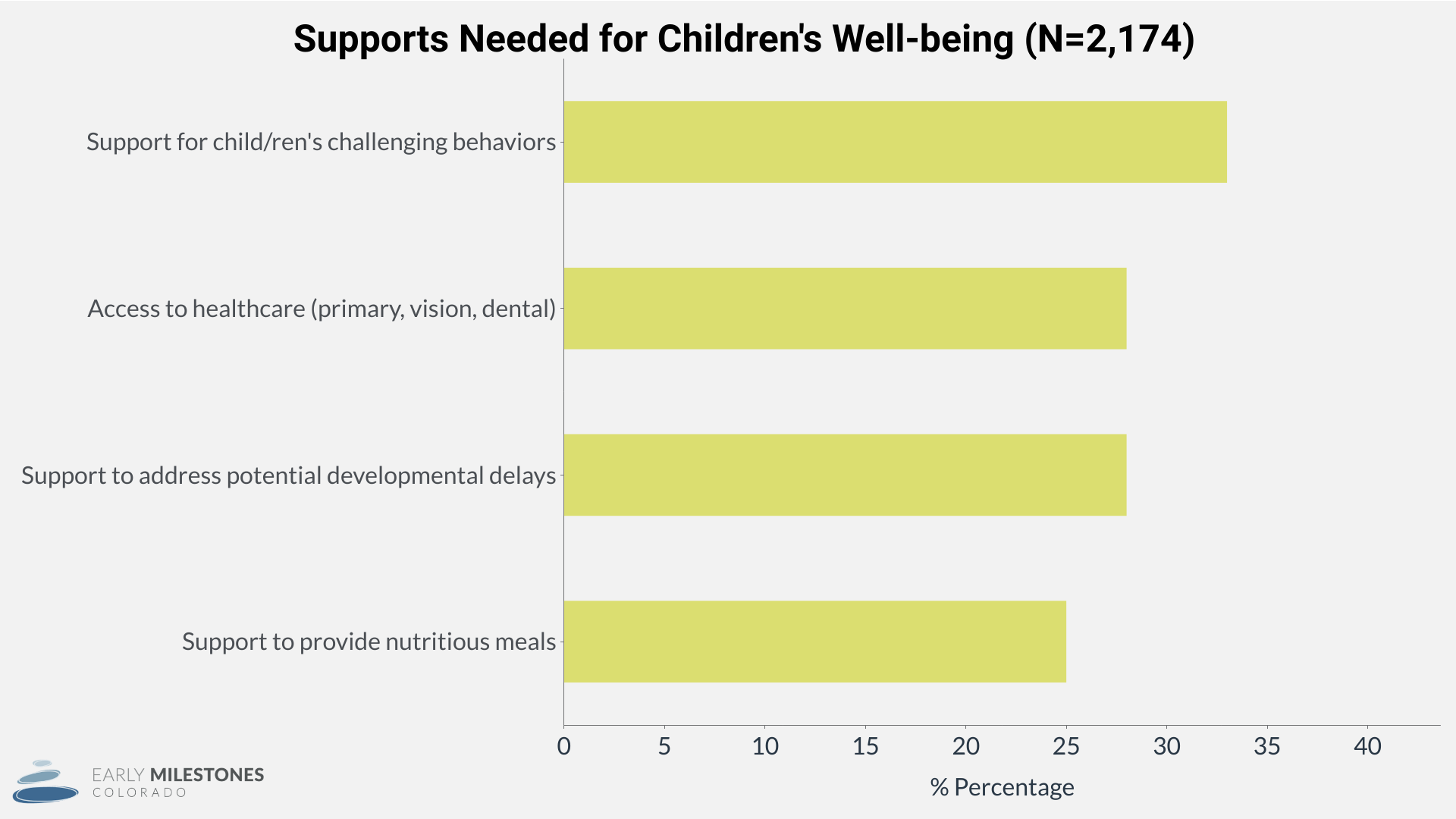

Learning loss during the pandemic and developmental delays were big concerns for Colorado families. When asked about their children’s well-being, 33% percent of parents said they need support for their children’s challenging behaviors. Twenty-eight percent wanted additional support to address potential speech, motor, or other developmental delays, and 25% of parents needed help providing nutritious meals for their children. Families also needed financial assistance, child care assistance, and mental health services for their children’s pandemic-related anxiety.

My daughter continues to have a great deal of anxiety about illness, germs, and loss. She is in therapy now. While I can’t say with certainty that her anxiety is caused by growing up during a pandemic, she does seem to focus on pandemic themes when she is worried. – White Mother, Broomfield County

Many families of young children felt left behind with changing attitudes towards pandemic precautions and lack of state and federal support.

While there has been some return to what life was like before COVID-19, the pandemic is not over. At the time of our survey, there had yet to be an approved vaccine for children under 5. Many families felt disconnected from those without small children who seemed to have returned to normal. This was especially true for families with immunocompromised children and family members.

“My daughter still doesn’t have a vax and my father is [immunocompromised], so we still avoid crowds…The new COVID guidelines basically say ‘[screw] the youngest ones and [the immunocompromised], you’re on your own.'” – White Mother, Pueblo County

“Society forgetting about the most vulnerable (like my son) in their efforts to get back to normal life. With all precautions gone in most places, my son cannot go anywhere.” – Hispanic/Latina Mother, Denver County

Additionally, families were disappointed to see pandemic support like the refundable Child Tax Credit and additional paid sick time expire.

“There is zero support for families of small children. No vaccines, no PTO, no childcare subsidy. And then massive inflation.” – White Mother, Denver County

“There is very little space in my work life as an educator to be flexible and stay home. Last year there was much more flexibility, but this year the expectation is that everything is back to ‘normal.’” – White Mother, Boulder County

Since the beginning, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted longstanding gaps in our social support systems. Nowhere was that more evident than for families with young children. As we continue to recover there is an opportunity to increase equity. State and federal governments, along with the private sector, can build better systems for societies’ youngest members and the people who care for them. Potential supports include increased financial assistance, workplace flexibility, and more responsive health systems that prioritize caregiver well-being.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Nicolaou, K., Delap, S., & Franko M. (2022) Sustaining & Adapting During the Pandemic: Colorado Families’ Experiences of Financial Instability. Denver, Colorado: Early Milestones Colorado.

[2] Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical child and family psychology review, 14(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1

[3] Crnic, K. A., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 117–132

[4] Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., Letterie, M., & Davis, M. M. (2020). Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics, 146(4), e2020016824. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-016824