Two first-time parents wait patiently at the doctor’s office. Their doctor enters and offers a summary of their test results. Their child shows early developmental delays. The doctor offers them some pamphlets. They must educate themselves about how to proceed.

Two first-time parents wait patiently at the doctor’s office. Their doctor enters and offers a summary of their test results. Their child shows early developmental delays. The doctor offers them some pamphlets. They must educate themselves about how to proceed.

Worried and afraid, both call family and friends for support as they process the news. Time passes, and after 40 weeks, they give birth to a baby girl. Despite challenges, the child’s reactions and mobility surpass the doctor’s expectations. “It’s a miracle,” everyone says.

In Mexican writer Guadalupe Nettel’s novel Still Born, miracles do not happen in isolation. The newborn baby’s survival depends not only on biology, but also on care and relationships. When their child’s health outcomes seem uncertain, both parents display exceptional courage.

When doctors lack understanding, the mother joins online forums to connect with others experiencing the same issues. There, she learns about a physiotherapist and a caretaker working with children with developmental delays. In this novel, life endures not because of formal healthcare services or health policy, but thanks to community infrastructure.

Nettel’s novel urges us to reconsider a question we often overlook: what does it truly take to sustain life?

The Infrastructure of Thriving

In Michelle Obama’s podcast with Craig Robinson, IMO, the former first lady makes a critical point about care. She says:

“We now have this crazy notion that we’re supposed to be this little unit of the family. Parents and children toughin’ it out together, you know, in some kind of isolation, when in fact, throughout humanity, that’s not how families were structured…There was always a big community.”

Michelle Obama knows that children thrive in contexts that foster interdependence. Parents and caretakers perform tremendous physical labor, like caregiving and household management. They are also planning, scheduling, making decisions, anticipating needs, supporting, teaching, and advocating.

Can you imagine the physical and mental toll of doing this alone? To me, the load seems tough to bear, but many parents do so masterfully. In 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that there were 10.9 million one-parent family groups with a child under 18.

The point is this: children thrive when their caretakers are supported. This means they must have access to quality healthcare to support maternal and child health. They must have affordable housing, childcare, education, financial opportunities, and community support. These interlocking elements are indispensable to sustaining life.

Yet our systems don’t always work. Barriers exist. A 2023 Early Milestones report found significant racial and economic disparities in healthcare access (Freeman Cenegy and Thornton). In 2016, 51% of Coloradoans lived in areas with a shortage or no licensed childcare for children under 5 (Center for American Progress). As of June 2025, most Americans (77%) reported that they feel economically insecure (Quiroz-Gutierrez).

In a time when political gridlock creates rising insecurity and stalls policy change, framing human thriving through the narrow lens of formal systems paints a bleak picture.

Who Picks Up the Pieces When Systems Fail?

When barriers to access exist and systems fail, life endures because of a tightly woven social fabric. The strength of our care infrastructure must be measured by the experiences of those who labor to sustain life from the margins.

Caring for children is deeply gendered and racialized. Emotional caretaking, domestic labor, and family planning are often unevenly distributed within households. These tasks fall disproportionately on women. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild famously referred to this unpaid labor as the “second shift”. Even though life cannot function without their labor, it often remains unacknowledged.

British scholar Emma Dowling has argued that we face a global care crisis. She shows how women of color from the Global South are migrating to more “affluent” countries to perform underpaid care labor. This reveals a care economy built on unequal exchanges of time, labor, and lives.

Yet other ways of organizing care exist. For instance, the lineage of Afro-descendent women of the Colombian Pacific region traces back to marooned communities who escaped colonial violence. Born out of extreme necessity and resistance, these women practice comadrazgo (co-motherhood). In an example of relational labor, they redistribute caretaking by cooking and caring for children collectively. These community-based practices ensure that thriving happens even in the face of systemic exclusion.

Shifting the Conversation on Systems Change

In the face of systemic failures, relational labor sustains life. Building truly sustainable care systems requires centering and supporting the informal networks that do this work every day. However, in many prominent approaches to systems change, policy is treated as the most effective tool for transformation.

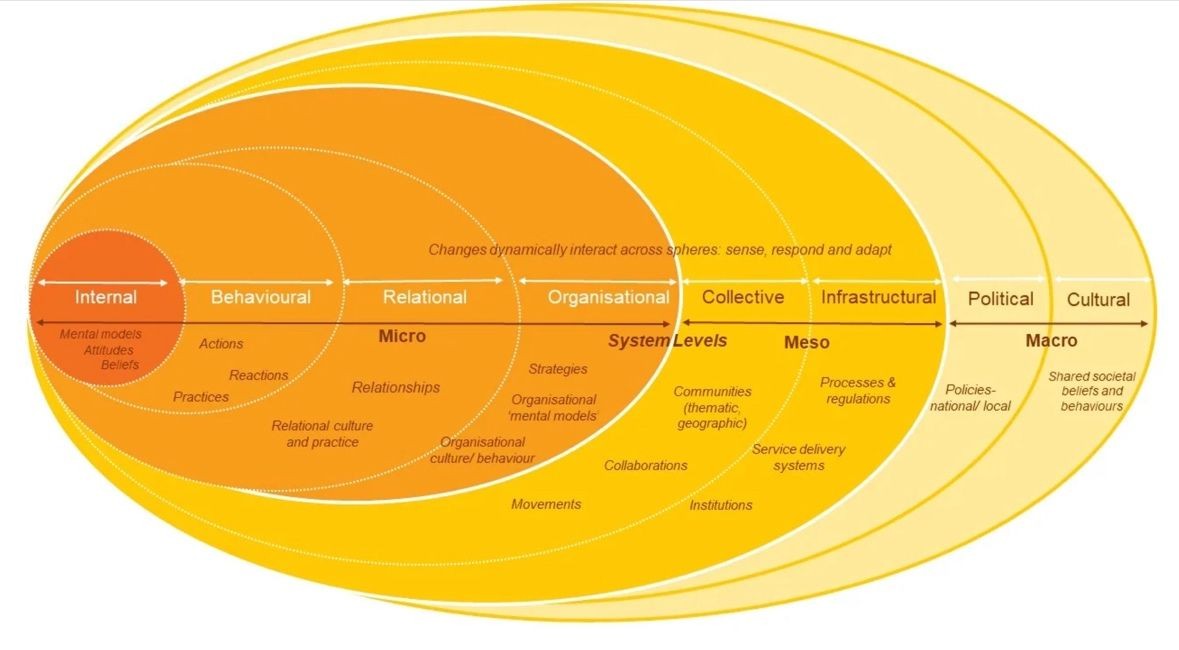

Let’s examine New Philanthropy Capital’s model of systems change below, for example. At first glance, policy might seem like a catch-all solution. It shapes internal, behavioral, relational, organizational, collective, and infrastructural change. Yet this is a misreading of the model. Positioned alongside politics in the model’s outer layer is something equally vital: culture.

Relational labor ties directly to culture. But if we continue to believe that life is most meaningfully improved through policy and formal systems, we will continue to direct our advocacy, funding, and imagination toward institutions alone. True systems change demands a broader lens, a shift in the conversation.

It means not only investing in programs and policy, but also learning how to listen, measure, and support cultural knowledge and strategy led by communities. It means looking at Nettel’s story and finding ways to advocate for young parents’ quality medical care and the quality of their connections to the community. Equally and simultaneously.

This is a process that begins with listening—truly listening—to those who have always known how to care for life in ways that institutions simply can’t. Let’s figure out how to measure our milestones based on that.

New Philanthropy Capital’s model of systems change (based on Broffenbrenner’s socioecological systems model)

keyTakeaways

The point is this: children thrive when their caretakers are supported. This means they must have access to quality healthcare to support maternal and child health. They must have affordable housing, childcare, education, financial opportunities, and community support. These interlocking elements are indispensable to sustaining life.

In the face of systemic failures, relational labor sustains life. Building truly sustainable care systems requires centering and supporting the informal networks that do this work every day.

True systems change demands a broader lens, a shift in the conversation. It means not only investing in programs and policy, but also learning how to listen, measure, and support cultural knowledge and strategy led by communities.

Early Milestones Colorado welcomes the expertise, insights, and latest research from across the early childhood system. We are thrilled to share guest blogs with our audience to advance critical knowledge and share vital perspectives. If you are interested in contributing a guest blog post, please email communications@earlymilestones.org.

Bibliography

Bureau, US Census. 2022. “Census Bureau Releases New Estimates on America’s Families and Living Arrangements.” Census.Gov. Accessed October 16, 2025. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/americas-families-and-living-arrangements.html.

Cenegy, Laura Freeman, and Courtney Thornton. 2023. “Young Children’s Health and Health Care Equity in Colorado.” Early Milestones Colorado. https://earlymilestones.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Young-Childrens-Health-and-Health-Care-Equity-in-Colorado_combined.pdf

Copeland, Joseph. 2025. “Most Americans Continue to Rate the U.S. Economy Negatively as Partisan Gap Widens.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/10/03/most-americans-continue-to-rate-the-us-economy-negatively-as-partisan-gap-widens/.

Lozano, Betty Ruth. 2022. “Feminism Cannot Be Single Because Women Are Diverse: Contributions to a Decolonial Black Feminism Stemming From the Experience of Black Women of the Colombian Pacific.” Translated by Daniela Paredes Grijalva. Hypatia 37 (3): 523–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2022.35.

Nettel, Guadalupe. 2023. Still Born. Translated by Rosalind Harvey. Fitzcarraldo Editions.

New Philanthropy Capital. n.d. “What is the Spheres of Systems Change Model?” Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.thinknpc.org/resource-hub/systems-practice-toolkit/spheres-of-systems-change/

Obama, Michelle and Craig Robinson. 2025. “IMO with Michelle Obama & Craig Robinson Full Episodes.” YouTube. Accessed October 16, 2025. http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL2wU-5VFkxvtgjdrTy9j0g2HmVRNaF4W1.

Quiroz-Gutierrez, Marco. 2025. “A quarter of Americans now say they need to make at least $150,000 to feel secure—and inflation is largely to blame.” Accessed October 23, 2025. https://fortune.com/2025/06/24/americans-not-financially-secure-inflation-perception-bankrate-survey/

Thornton, Courtney. 2024. Building an Equitable Early Care and Learning System in Colorado. Early Milestones Colorado. https://earlymilestones.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Building-an-Equitable-Early-Care-and-Learning-System-in-Colorado_FINAL.pdf.